Many FileMaker developers do not typically include robust error trapping and handling in their solutions. This can have important adverse implications in terms of security, data integrity, and user experience.

In this two-part blog post, we will explore the following:

- Why and when to trap for errors

- Why many of us don’t implement thorough error trapping, and what we can do about it

- A specific technique developed by this blog post’s author to easily trap for and handle errors, akin to the notions of try-catch blocks, throwing errors, and stack trace, which are commonly used in source code programming languages

Assertions and Error Trapping as a Mindset and Habit

Unexpected conditions at runtime are to be expected for any computer program. They may result from end users interacting with our apps in ways that we did not anticipate; it may be that a malicious actor tries to break into our solution, etc. As developers, it is our responsibility to account for such conditions in the code that we write. The way to do so is by asserting (aka validating) that the necessary conditions for our app to execute as expected are present, and to trap for and handle errors when the program encounters unexpected conditions.

Whereas my formal background is in Agronomy, Animal Sciences, and Economics, in 2012 and 2013, I took some classes at the Computer Science department at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. During that time, I attended a workshop on Software Debugging by Perry Kivolowitz. Perry has worked as a faculty member in different Computer Science departments, and is an Academy Award winner for engineering inventions used in films like Forrest Gump and Titanic.

During that workshop, he told the audience that he would execute a program that he had written, and then start randomly hitting keys on the keyboard like a madman, just to see how the program responded under unexpected runtime conditions. The image of him banging at the keyboard to try to make the program crash was an effective way of driving the point home, as that visual has stuck with me to this day.

The point he was making is also captured in the Defensive Programming approach, and in a nutshell is this: write code assuming that there will be unexpected inputs and other unexpected conditions at runtime. Given that, assert the conditions expected by the program, trap for errors, and handle errors such that your code fails gracefully under unexpected conditions.

For background purposes, here are some resources that describe the defensive programming approach:

Assertions and Error Trapping Example

If the notions of assertions and error trapping are new to you, here is an example that illustrates these points:

Say scriptA accepts a param that represents a line item ID (Serial Number field), which it uses to find the corresponding LineItem record and then delete it. Let’s also assume that the LineItem::ID field has a field-level validation that makes that field unique.

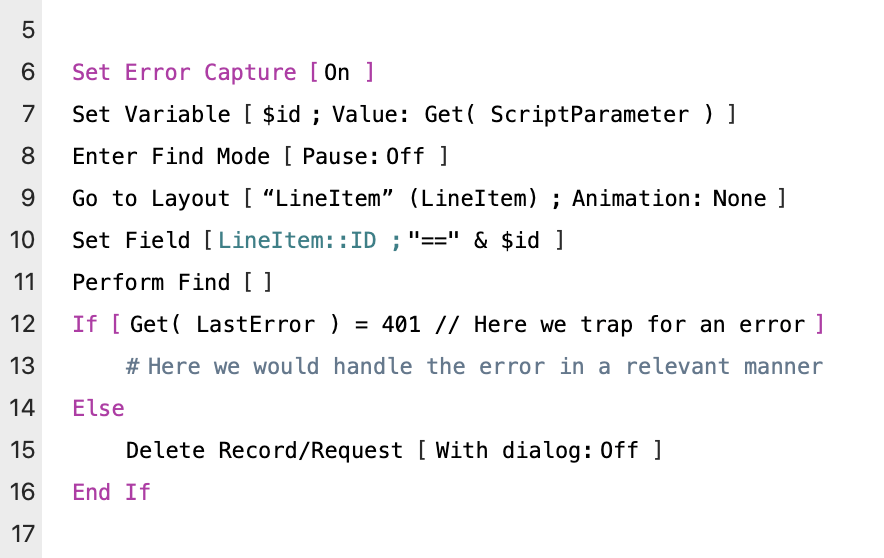

We could write scriptA as follows:

The script goes to the LineItem layout, uses the “==” operator to ensure an exact match in the find, which, together with the fact that field LineItem::ID has a “unique” validation specified, should result in the find returning either 0 or 1 records. After performing the find, we check for FileMaker error code 401 (No records found). If that error occurs, we handle the error in an appropriate manner; otherwise, we delete the record.

Does this look like a script that you would write? Does it seem like a fine way of finding a record and checking for errors before deleting the record, if one was found?

Consider this scenario: if the param passed into scriptA is “*”, the Perform Find step in line 11 results in a found set of all records in the LineItem table (unsorted), and Get( LastError ) in line 12 returns 0. In this case, the first record in the LineItem table would be deleted.

Actually, there is no guarantee of that. The script assumes that the Go to Layout step in line 9 succeeds. If it does not, because, say, the layout was accidentally deleted, that script step will fail, and scriptA would continue to execute in whatever layout it was called from. In that case, the Perform Find step returns error code 103 (Relationship is missing), which is different than the specific 401 error code that the script checks for. Thus, the script will go into the Else branch of the If block, and whatever record was being browsed in the table that the original layout is based on will be deleted.

Furthermore, even if a valid line item ID value is passed into scriptA, and even if navigation to the layout LineItem works as expected, there is no guarantee that scriptA will find 1 and only 1 LineItem record. When you create a new table in FileMaker, 5 fields are created automatically for you, one of them being “PrimaryKey”, which has the “Not empty” and “Unique value” validations checked. However, those validations are NOT always enforced, as the “Only during data entry” option is checked by default, NOT the “Always” option. If you did not change that default setting for your primary key field, or if, for whatever reason, you have duplicate LineItem records, scriptA could also end up deleting the wrong record if multiple records are found.

You might say, “Well, that’s a contrived example.” To which I would counter: “Has an end user ever used any feature in an app that you wrote, in a way that you did not expect they would?”. And have you heard of “hackers” and “security breaches”?

If you are not asserting conditions and trapping for errors in your solutions, you are operating based on faith. You are hoping that the conditions under which your scripts get executed are what you expect them or envisioned them to be. This is a dangerous situation to put oneself in when writing computer programs, as unforeseen runtime conditions are to be expected. Furthermore, I would argue that we should write applications expecting that someone will try to break them, or break into them.

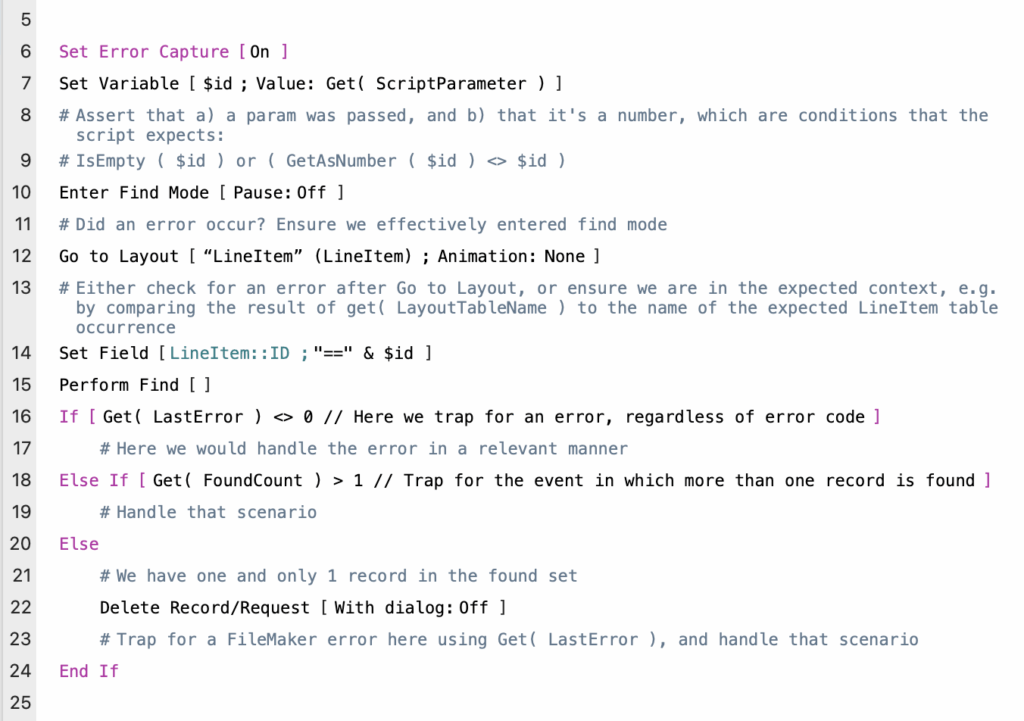

Here is a revised version of scriptA, with assertion expressions, comments, and additional error trapping added (this is not a fully functional script, I am purposely avoiding including fully functional code to add assertions and error trapping yet, as that will be the focus of part two of this blog post series):

Why do software applications crash? Typically, because unforeseen circumstances are not handled correctly or gracefully by the code. Why do applications and systems get hacked? Because doors are left open for a malicious actor to get in.

Why We Do Not Error Trap

Things like not validating inputs into our scripts can open the door to our apps getting hacked. Not trapping for errors can lead to our app crashing, or leave the app in a state that exposes information that users should not have access to. Still, many of us don’t write code that properly addresses these types of scenarios. Next, I’ll discuss a few reasons why we don’t.

Lack of exposure to techniques to error trap

FileMaker Pro does not expose common programming mechanisms, such as try-catch blocks, the ability to throw exceptions, etc. Therefore, FileMaker developers who have not had exposure to other programming languages simply are not familiar with such concepts.

Whereas FileMaker gives us the ability to check if an error occurred, via functions such as Get( LastError ), there is no built-in mechanism in the platform to define our own errors, “throw” an error or exception when an error occurs, or “catch” an error when one occurs.

This tends to result in developers implementing error trapping mechanisms that lack consistency and robustness (if implemented at all).

My app does not require error trapping

One misconception is that unless we are writing an app for a client with extremely low tolerance for failures, like an app that processes financial transactions, an app used in medical procedures, or in a space shuttle, robust error trapping and handling is just not necessary or worth it.

Error trapping makes my code too long and cluttered

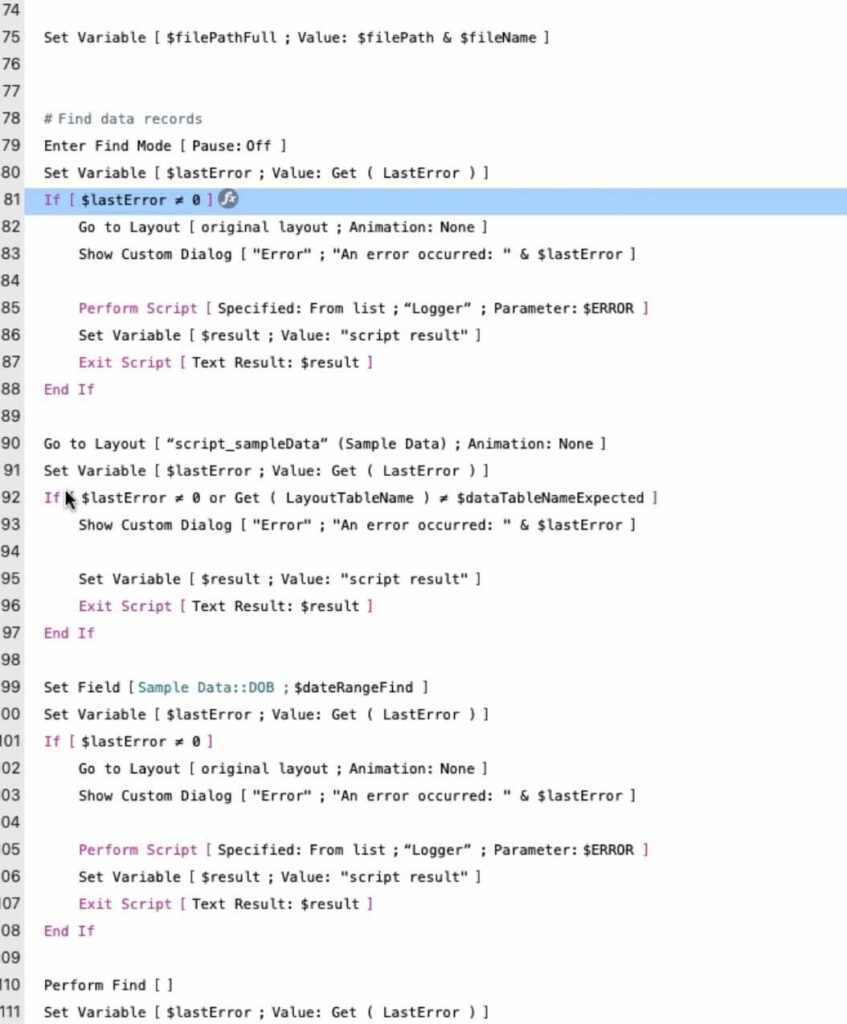

In the absence of an efficient error trapping technique, adding various assertions and error traps can result in our scripts ballooning in size, and also make it harder to maintain and understand such scripts. We can also end up with a lot of duplicated code. Here is an example of a script in which we are checking for an error after every step that could result in an error, and in every error check block, showing a custom dialog, calling a logger script, and exiting the script:

This script is hard to read and maintain. This is not an efficient way of implementing error trapping and handling.

Not enough budget / will delay delivery of app

Another misconception is that robust error trapping and handling will necessarily blow out the budget for a project, and/or extend the calendar time for product delivery. If we were to reinvent the wheel and craft from scratch a thorough error trapping mechanism in FileMaker, that would increase the level of effort on a project. However, utilizing a tried and proven error trapping approach and technique can have the opposite impact; it can effectively save time. It will definitely result in the end product being a much more robust application.

Innovative Error Trapping Technique

Implementing thorough validations and error trapping, as mentioned before, can actually save time. For this to be true, however, we need to have a well-defined, convenient, and fast way of adding validations and error trapping to our solutions. Depending on your current development practices, this may also involve a bit of a paradigm shift in how you structure your scripts, namely, having a single exit point when an error occurs.

Whereas the different components of the Claris platform are written in programming languages that natively provide a means to throw and catch exceptions, generate a stack trace, etc. – and Claris engineers rely on such constructs – that functionality is not exposed to FileMaker developers.

That is where “clew” comes in. clew is a systematic way of easily implementing robust assertions and error trapping in FileMaker solutions. It is comprised of a suite of custom functions that also capture a trace of script calls and errors, and state information for each script in the call stack. That error trace can be a most powerful troubleshooting aid, especially when we have script chains that are multiple levels deep.

No schema, scripts, layouts, or plugins are required by clew, just a suite of custom functions, of which we normally use 10 or so functions in most of the code that we write. We also tend to rely on a script template that contains snippets of these functions “in action”, which we can easily copy and paste into new scripts, so that we don’t have to write common script blocks from scratch every time. Clew is free to use and open source.

In part two of this blog post series, we’ll take a deep dive into how clew works, and how we use it to write more secure and robust FileMaker applications, without it taking us any longer to write such apps.

If you have any questions or are interested in partnering with our team on your FileMaker application, contact us today.

Thanks Marcello for raising this topic and I’m looking forward to reading about clew.

FileMaker’s easy but rudimentary scripting always leaves me in two minds about whether to just give up on it and do all the business logic in a Python microservice, and, at the very least, provide a microservice which could run (one of the many) JSON schema validators against every FM script’s input parameter, just for sanity.

As OData gradually comes closer to Draco, if I understand correctly, I feel maybe to just use Python first, or other preferred language, and confine all the FM scripts to just doing the interface layer’s functionality.

Ciao Stefano, thank you for your comment. Whereas we write web services to use with some of our FM apps, the web service logic typically complements or extends the business logic captured in FM scripts, it’s not a replacement for it.

A “native” mechanism for throwing and catching exceptions/errors, and for defining errors, is something missing in FM scripts, and that’s why I wrote clew. I’m curious in what other ways you find FM scripts to be lacking, such that you consider only using them to drive “interface” (UI?) functionality, and you lean towards writing all business logic in a web service?

You can expect part 2 – the actual dive into clew – of this 2-part series to be published this coming week. I would be most curious to learn if clew makes you reconsider your approach to FM scripts at all, or not. Please comment again once part 2 is published and let me know your thoughts!